Dr John Fleming talks about the Middle Ages and the modern world, part 3

Part 1

Part 2

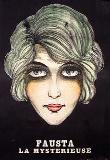

F And the character really makes you think as a reader what your beliefs are, too. I thought that was one of the better Tales. However, reading the Canterbury Tales, I was very impressed that there was so much money that people could actually forego earnings and go on pilgrimages. The Wife of Bath basically spent her life travelling from one pigrimage to another.

JF: Well, Fausta, the Wife of Bath was very rich because she had, unlike you and other nice girls, married very strategically. She had married, if you remember, a series of old geezers who were quite rich and who conveniently died right away -with her help, probably, I wouldn't want to be married to the Wife of Bath, but she had inherited a lot of property. If you remember, the husband she loves most and has the knock-down, dragged-out fight with, when they have the slogging match she says, "Oh, it's for my land that you have murdered me". He obviously owns some possessions.

It's quite true. I think people did impoverish themselves sometimes to go on pilgrimages. It is thought by some economic historians that one of the problems with the Medieval economy was that there were so many people who were, in effect, non-producers, either living in religious houses, hermits, or as you say wondering around all the time.

But Medieval poverty was different from modern poverty. Look at St Francis: he founded his order on the concept of what he called evangelical poverty, because in his readings of the Scripture Christ was a very poor man who, according to his interpretation, owned absolutely nothing at all. So that poverty which was voluntary was a theological virtue. What we call poverty, which of course is poverty, is a terrible social disaster. There were such people too, in the Middle Ages, but they were thought of as the absolutely necessary recipients of social charity. This is what the word hospital actually means: a place where you provide hospitality to a traveler, a pilgrim, a poor person, a sick person even, and that's how the word came to its meaning today.

F: [That's] interesting about the number of non-productive people because you tend to think that a monastery would come to be a place of industry of some sort just because they had to support so many people.

JF: Many of them were, but the problem is that it doesn't take very long for idealism to crash up against the rocks of social reality.

We see this in monastic history all the time, that is to say, you get a religious reformer, this is very brilliantly exemplified by the rise of the Cistercian order - with whom we associate St Bernard and other famous saints in the 12th Century. These guys moved out into the deep countryside because they didn't want to be around. They wanted to get away from snares and delusions of the world. Rich landowners often gave them land that they thought was without value, not good agricultural land out in the wilderness. Then in the 13th Century, particularly in England, there's a tremendous development of the wool trade, textiles, now, wool is made from sheep, sheep like to eat grass, so that these vast holdings, and some of the monasteries are now very valuable property. And suddenly they're rich people and they start out to be professional paupers and end up as rich people just like the people they're trying to get away from.

Nothing fails, Fausta, like success.

F: So is that what the Middle Ages teach us?

JF: Well, that's certainly not the final thing it teaches. The Middle Ages has, what I find, incredible, and in many ways, admirable cultural coherence. But of course it does that at the expense of other values that in our age we've come to appreciate much more greatly, so-called multicultural values. The values of actual cultural, religious, intellectual diversity.

This is a big problem with culture altogether. The tension between that core commonality that holds people together and the danger that that very commonality can turn into a source of discord or ethnic strife, whatever it may be, the stuff we see every day in the front pages of the New York Times.

F: Thank you very much Dr. Fleming.

Copyright 2007 Fausta Wertz, John Fleming

John V. Fleming is the author of

Labels: Blog Talk Radio, books, history, literature, movies, podcasts

3 Comments:

Thank you Fausta. Priceless!

Thank you Fausta. Priceless!

Thank you Fausta. Priceless!

Post a Comment

<< Home